The Kentucky Explorer -- October 2010 -- Page 47

A Young Boy Returns A Lost Pigeon And Visits Heitzman's Loft

Author's Note: This is a true story about Charles Heitzman, the owner of the Heitzman Bakeries in Louisville, Jefferson County, Kentucky. He is known as Kentucky's finest pigeon flier. I was honored when a young boy to see his trophy room and library.

E. Lowell "No Sweat" Robbins, Jr. - 2010

I was sitting in the middle of the back seat of my grandfather's new 1961 white Chevrolet Impala four-door sedan headed west from Irvine, Estill County, Kentucky, to some place outside Louisville, Jefferson County, called Jeffersontown. My grandfather was driving, and Herman was riding shotgun. Herman ran the projectors at Grandfather's theater in Irvine. Though small in stature, my grandfather was anything but. He'd long been taking care of Herman's family, making certain they always had a roof over their heads. together, those two were quite the team, not because of work but because of the lifelong bond they owned for each other. By luck I had wound up in their mix.

My grandfather looked like Dwight Eisenhower, only softer. Every day he would learn a new word and go over it with me. He said that education was something no one could ever take from me. In my lap was a box holding the pigeon I'd caught under the bridge at Irvine. Because of the name and address band on one of its legs, my grandfather had been able to locate its owner, Charles Paul Heitzman, of Jefferson-town. When my grandfather called him, Mr. Heitzman was thankful that the bird had been found. It had been in a special race for young pigeons, being some 300 miles in distance and had gotten caught in one of our Kentucky storms that kept the frogs hushed through the night. Not a single pigeon of some 300 had made it home. The bad weather had continued for several days and the bird had given up hopes of home and resolved to survive, finding refuge among the bridge's common pigeons; a bridge, near my front yard, that spanned over the Kentucky River.

After some pleasant thoughts and conversation, we were on the outskirts of Jeffersontown and on a small drive that went over a creek and on to a private bridge having stonework with arched sides. Once over the bridge, a bricked driveway led to a sprawling estate that was set comfortably in the countryside. Driving by a porcelain statue of a hand-painted racing pigeon that was mounted atop a stone obelisk, the word "Heitzman" with bold letters reflected under it. The Impala soon parked in a circular driveway. There waiting was a small man of average build, about the same age as my grandfather, wearing a short-sleeved, white dress shirt and pale-colored pants with a small black belt that owned a tongue hanging several inches below its buckle. The man's white hair, though slightly messed, was trimmed and combed neatly back and over to one side. His dark framed eyes held in careful study. There was something serious and at the same time almost Santa Claus about the figure.

"I'm Charles Heitzman," spoke the man, giving my grandfather a firm handshake. The two men were much alike; respectful, unpretentious and genuinely warm. "There are no strangers in this world," spoke Heitzman, "Only friends we've yet to meet." In that handshake I somehow gained another grandfather.

Mr. and Mrs. Charles Heitzman of Jeffersontown KY, who celebrated their Golden 50th wedding anniversary on January 25, 1970. They are the parents of one son, Charles, Jr, and three daughters, Mary Agnes, Bernice and Dorothy. They have fourteen grandchildren. This picture first appeared in the ARPN, February, 1970.

I handed Mr. Heitzman the box with the pigeon. He examined the bird, looking at the bands on its legs. "Come on and I'll show you Cedar Point," he said, turning and walking along a sidewalk that led toward the rear of his home. "Before you see my lofts, I want you to see my library."

I handed Mr. Heitzman the box with the pigeon. He examined the bird, looking at the bands on its legs. "Come on and I'll show you Cedar Point," he said, turning and walking along a sidewalk that led toward the rear of his home. "Before you see my lofts, I want you to see my library."

We passed by a large bell mounted near the back door of Mr. Heitzman's tiled roof home. He explained that Agnes, his wife, would ring the bell when she wanted him to come in from the lofts to answer the phone or have a bite to eat. The walkway continued through a row of mature red cedars facing each other and up a hill to a tan block building with white awnings and nest boxes for wrens on each side of a door that owned a large metal "H" in its center. In front of the building to its left were trimmed hemlock hedges, and to the right were statues and head markers of four of Mr. Heitzman's deceased racing champions: "Heat Wave," "Hei Times," "Head Wind," and "Hurry Home." Close by, a clearing in the middle of a lawn facing an assemblage of some 20 racing lofts, was a silver sphere glistening in the sun. "What's that?" I asked.

"My beacon. It helps guide my birds in on a close race. They can spot it 20 miles out. Andy Devine was here last month. He asked that same question.

"Andy Devine?" asked my grandfather, rather curious. "The movie star," informed Mr. Heitzman. "he was Buck, the stagecoach driver in Stagecoach. John Wayne was Ringo. Andy said that John Ford directed that movie and that he's making another one with John Wayne and himself called The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance. They're supposed to start shooting it this month."

A group of racers flew powerfully by, diving, twisting, and darting while their wings whistled. The purple martins in their many boxes close by cocked their heads, watching as well. A stranger in paradise? I stood there in wonder. Those pigeons on the Irvine bridge, that I lived near, could fly and do so many things in the sky, but these pigeons were brilliant, in control, toying with gravity, showing off among each other, and smiling all the while.

Mr. Heitzman looked at me as I watched the racers pass overhead. A few of the pigeons left the main flock on each pass and dropped from the air as they lowered their legs and changed their flight to land on a branch of a poplar tree. The tree dazzled with them.

"When Andy was about your age," Mr. Heitzman informed, "he had a cat that kept coming around his loft, killing his birds. Andy lived out in Arizona near a mining town and could get plenty of dynamite. When he trapped that cat, he and one of his friends tied four sticks of dynamite to it and lit the fuse and then took off running. It ran straight under Andy's pigeon loft, blew up the building, and killed every bird."

A giant black and white photo of a man with a long white mustache, standing in front of a two-story building, greeted us when we entered the library. Mr. Heitzman stood by a fireplace and identified the man in the photo as Paul Sion. Sion lived in Tourcoing, France. His pigeon loft was built above his home.

Mr. Heitzman asked that his leather bound guest book be signed. Inside it, among its names were Yul Brynner, actor; Carlo Napolitano, loft manager of H. M.; the Queen of England; and Rex Ellsworth, breeder of Swaps, the Kentucky Derby winner. "Rex and I share one rule: the apple never falls far from the tree. Swaps is down from Man O'War. From the best you get the best."

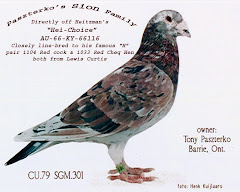

Covering all four walls and throughout the building were racing pigeon items as well as every book ever written on them. The books went on and on. Some being published in the 1860's. Along with the books were the leading magazines from nearly every country in the world, foremost being The American Racing Pigeon News, the monthly published in the USA and the The Racing Pigeon Bulletin, the oldest and leading weekly. Standing atop a desk was an old wicker basket. "My first Sions (pigeons) were shipped to me in that basket," spoke Mr. Heitzman.

"Who is Sion?" I asked.

"He was a man that was once a boy like you," answered Mr. Heitzman." When he was your age he visited a man named Wegge. From him, Sion got his start. That was back when the breed was just beginning. Paul Sion became the greatest flier in France, then, the world. When I began to make a little money, I wanted the best racing pigeons and sought him. Those birds have made me, and they've kept me alive."

I knew what my grandfather was thinking when Mr. Heitzman had spoken. The past week, he had shown a movie, The birdman of Alcatraz, starring Burt Lancaster, Karl Malden, Thelma Ritter, Neville Brand, Telly Savalas, and Edmond O'Brien. It was a touching story about a hardened inmate's life suddenly changing when he rescues a baby sparrow in a storm. My grandfather had talked to me about how the inmate had saved the bird and in return the bird had saved him.

"What business are you in?" asked my Grandfather.

"Bakery. My father came over from Germany and started the business. He spelled his name with two (h)s. The truck that once owned all he had is under my main racing loft. You can stand it on its end, and when you open it, its a closet."

In the library on one wall was a plaque from The National Pigeon Association naming Mr. Heitzman an "All American." There were over 100 silver and bronze trophies and plaques that Mr. Heitzman had on display. These were only his major awards.

There were also several Belgium made, wooden, box-like seven-day racing clocks and a metal, two bird, two-day racing clock that was made before the turn of the century. I saw many paintings of his champion racers, the mounted banded legs of his foundation birds that died many years ago, and two white loft coats embroidered with the words "Heitzman Lofts."

I saw plastic and aluminum tubular message carriers that had been used in WWII; a detailed pen and ink sketch of Mr. Heitzman's main racing loft; a wooden model of one of his breeding lofts, complete with its miniature dowel aviary; a maroon sweater sent to him from Tokyo, with the image of a racing pigeon sewn into it; a porcelain ashtray with the colored image of his famous racer, "Hei Pockets," crafted into it; many statues that were replicas of his famous fliers; and professional photographs of his birds as they flew. Among the photographs were scenes of his estate from the air, his birds in perfect stances, and incredibly detailed pedigrees done in Mr. Heitzman's masterful handwriting, with such exquisite penmanship, as if done by God's own scribe using a feather from the best racer. In one area was a completed card file written for every bird he had bred since 1919.

Mr. Heitzman stepped outside. "Come on," he urged, opening the door. "I'll show you around."

We began walking along the neatly mowed bluegrass lawn passing one breeding loft to our right as we went over a slope towards the main racing loft that was built high up off the ground. It owned green painted latticework around its base and white steps with white concrete urns leading up to its middle doweled and screened front door, possessing the words "Charles Paul Heitzman" in white against a black metal background. Just out from the eves of the loft along the front of its large and rectangular structure, Mr. Heitzman opened windows leading to tip doweled aviaries that owned landing boards. These were the airstrips for his winged thoroughbreds.

The place was magical. Many of the birds flew down from their individual box perches to go to the floor. They stretched their bodies, looking up, spreading their wings, all but speaking to Mr. Heitzman, expressing trust, saying, "We're hungry!"

Those birds were his babies.

Several of the birds were nearly solid red in color, actually maroon. Some of them were almost white, marked with two tan colored bars across their wings. Then a bird that was light grey marked with two wide black bars across its wing flew near. "That one is like the one I brought back to you," I commented.

"That color is called a 'blue bar,'" informed Mr. Heitzman. "Sion had a great racer colored like that named Napoleon. All pigeons are descended from that color from a bird that lived along cliffs called the wild blue rock dove. There's two color genes in pigeons, red and black. The black gene is recessive to the red. The pigeons colored with bars are recessive to those that have checks or other markings on their wings. A blue bar is recessive in its color and also in its markings, but when a blue bar mates with a blue bar, blue bar babies will always be produced. You see, when two recessives mate, that trait then becomes dominant. It wasn't finches that inspired Charles Darwin in his Origin of Species. It was pigeons. Darwin wrote a sonnet to them. I used to know it. He wanted a sense of how much variety existed with a single type of animal. At one time he had over 100 pigeons. When his daughter's cat got into his loft, he had the cat killed. He belonged to a prestigious pigeon club. A person had to be voted on by its members in order to be admitted. He wanted to show that a new species could be created from a common ancestor by the accumulation of small changes over generations. He believed that studying artificial selection of animals like pigeons would provide the evidence.

Mr. Heitzman's records were so complete that he could tell before two babies hatch, what colors they would be and everything about them. The most important thing to breed for is instinct. When a bird is found with that strong homing instinct and combined with condition, it will be a champion. Race horse people know and do the same thing.

Mr. Heitzman went over to one of his feed bins and lifted its cover and scooped out some mixed feed, spreading it inside a wooden, trough-like feed tray on the floor. The birds' beaks began pecking at individual seeds. There was a unison of pecking noises and heads bobbing with every bird hustling to gain a strategic position to eat. Each head was as quick as fingers racing in a typing class.

Mr. Heitzman went back out the door and down the steps with us following. We met an elderly man dressed in overalls, wearing a tilted blue and white striped engineer's cap. Mr. Heitzman introduced him as his full-time employed loft keeper. The man had been with Mr. Heitzman just like Herman had been with my grandfather. Mr. Heitzman asked that he grate a head of cabbage and meet us in the main stock loft. Walking on down over the hill towards a stand of woods along a creek, the stock loft appeared as though some tranquil home for the elves. It owned a round roof with a doweled aviary protruding from the front of it. The loft entered from the side, stepping through two doors. "The bird you caught will go in here," spoke Mr. Heitzman. "I already know who I will mate him to next year. I keep the males and females separated from July to February. I put them together on Valentine's day. Following nature is always best. I'm line breeding him back to Sion's Napoleon. It has been so long since a bird has been returned to me. When someone sees 'KY' on a bird's leg, he know its mine. I've had the KY bands since the end of the war. The American Racing Pigeon Union issues them solely to me. If one of my birds traps into another loft, I never hear about it. I suppose that's a compliment."

"My grandson is wanting to build a loft. Do you have any suggestions?" asked Grandfather.

"Lofts don't need to be big or heavy. My son flew pigeons in the Signal Corps during the war. Many of the birds I donated. They used portable lofts, and their birds stayed fine. Some of my favorite lofts in the back are from the war. Make your loft out of wood. You don't want concrete block, it will sweat. Moisture promotes sickness. Keep the loft off the ground. Make certain its well ventilated and face it to the south," Mr. Heitzman explained.

"How much do you get for a pair of pigeons?" asked Grandfather.

"A hundred dollars a pair for young birds. More for the old birds. If you all will come back next summer. I'll give you four youngsters. One out of the bird you returned. You'll never get better than that."

E. Lowell Robbins, Jr., 207 Longview Drive, Richmond, KY 40475; rrobbins6@juno.com, shares this article with our readers.

"My beacon. It helps guide my birds in on a close race. They can spot it 20 miles out. Andy Devine was here last month. He asked that same question.

"Andy Devine?" asked my grandfather, rather curious. "The movie star," informed Mr. Heitzman. "he was Buck, the stagecoach driver in Stagecoach. John Wayne was Ringo. Andy said that John Ford directed that movie and that he's making another one with John Wayne and himself called The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance. They're supposed to start shooting it this month."

A group of racers flew powerfully by, diving, twisting, and darting while their wings whistled. The purple martins in their many boxes close by cocked their heads, watching as well. A stranger in paradise? I stood there in wonder. Those pigeons on the Irvine bridge, that I lived near, could fly and do so many things in the sky, but these pigeons were brilliant, in control, toying with gravity, showing off among each other, and smiling all the while.

Mr. Heitzman looked at me as I watched the racers pass overhead. A few of the pigeons left the main flock on each pass and dropped from the air as they lowered their legs and changed their flight to land on a branch of a poplar tree. The tree dazzled with them.

"When Andy was about your age," Mr. Heitzman informed, "he had a cat that kept coming around his loft, killing his birds. Andy lived out in Arizona near a mining town and could get plenty of dynamite. When he trapped that cat, he and one of his friends tied four sticks of dynamite to it and lit the fuse and then took off running. It ran straight under Andy's pigeon loft, blew up the building, and killed every bird."

A giant black and white photo of a man with a long white mustache, standing in front of a two-story building, greeted us when we entered the library. Mr. Heitzman stood by a fireplace and identified the man in the photo as Paul Sion. Sion lived in Tourcoing, France. His pigeon loft was built above his home.

Mr. Heitzman asked that his leather bound guest book be signed. Inside it, among its names were Yul Brynner, actor; Carlo Napolitano, loft manager of H. M.; the Queen of England; and Rex Ellsworth, breeder of Swaps, the Kentucky Derby winner. "Rex and I share one rule: the apple never falls far from the tree. Swaps is down from Man O'War. From the best you get the best."

Covering all four walls and throughout the building were racing pigeon items as well as every book ever written on them. The books went on and on. Some being published in the 1860's. Along with the books were the leading magazines from nearly every country in the world, foremost being The American Racing Pigeon News, the monthly published in the USA and the The Racing Pigeon Bulletin, the oldest and leading weekly. Standing atop a desk was an old wicker basket. "My first Sions (pigeons) were shipped to me in that basket," spoke Mr. Heitzman.

"Who is Sion?" I asked.

"He was a man that was once a boy like you," answered Mr. Heitzman." When he was your age he visited a man named Wegge. From him, Sion got his start. That was back when the breed was just beginning. Paul Sion became the greatest flier in France, then, the world. When I began to make a little money, I wanted the best racing pigeons and sought him. Those birds have made me, and they've kept me alive."

I knew what my grandfather was thinking when Mr. Heitzman had spoken. The past week, he had shown a movie, The birdman of Alcatraz, starring Burt Lancaster, Karl Malden, Thelma Ritter, Neville Brand, Telly Savalas, and Edmond O'Brien. It was a touching story about a hardened inmate's life suddenly changing when he rescues a baby sparrow in a storm. My grandfather had talked to me about how the inmate had saved the bird and in return the bird had saved him.

"What business are you in?" asked my Grandfather.

"Bakery. My father came over from Germany and started the business. He spelled his name with two (h)s. The truck that once owned all he had is under my main racing loft. You can stand it on its end, and when you open it, its a closet."

In the library on one wall was a plaque from The National Pigeon Association naming Mr. Heitzman an "All American." There were over 100 silver and bronze trophies and plaques that Mr. Heitzman had on display. These were only his major awards.

There were also several Belgium made, wooden, box-like seven-day racing clocks and a metal, two bird, two-day racing clock that was made before the turn of the century. I saw many paintings of his champion racers, the mounted banded legs of his foundation birds that died many years ago, and two white loft coats embroidered with the words "Heitzman Lofts."

I saw plastic and aluminum tubular message carriers that had been used in WWII; a detailed pen and ink sketch of Mr. Heitzman's main racing loft; a wooden model of one of his breeding lofts, complete with its miniature dowel aviary; a maroon sweater sent to him from Tokyo, with the image of a racing pigeon sewn into it; a porcelain ashtray with the colored image of his famous racer, "Hei Pockets," crafted into it; many statues that were replicas of his famous fliers; and professional photographs of his birds as they flew. Among the photographs were scenes of his estate from the air, his birds in perfect stances, and incredibly detailed pedigrees done in Mr. Heitzman's masterful handwriting, with such exquisite penmanship, as if done by God's own scribe using a feather from the best racer. In one area was a completed card file written for every bird he had bred since 1919.

Mr. Heitzman stepped outside. "Come on," he urged, opening the door. "I'll show you around."

We began walking along the neatly mowed bluegrass lawn passing one breeding loft to our right as we went over a slope towards the main racing loft that was built high up off the ground. It owned green painted latticework around its base and white steps with white concrete urns leading up to its middle doweled and screened front door, possessing the words "Charles Paul Heitzman" in white against a black metal background. Just out from the eves of the loft along the front of its large and rectangular structure, Mr. Heitzman opened windows leading to tip doweled aviaries that owned landing boards. These were the airstrips for his winged thoroughbreds.

The place was magical. Many of the birds flew down from their individual box perches to go to the floor. They stretched their bodies, looking up, spreading their wings, all but speaking to Mr. Heitzman, expressing trust, saying, "We're hungry!"

Those birds were his babies.

Several of the birds were nearly solid red in color, actually maroon. Some of them were almost white, marked with two tan colored bars across their wings. Then a bird that was light grey marked with two wide black bars across its wing flew near. "That one is like the one I brought back to you," I commented.

"That color is called a 'blue bar,'" informed Mr. Heitzman. "Sion had a great racer colored like that named Napoleon. All pigeons are descended from that color from a bird that lived along cliffs called the wild blue rock dove. There's two color genes in pigeons, red and black. The black gene is recessive to the red. The pigeons colored with bars are recessive to those that have checks or other markings on their wings. A blue bar is recessive in its color and also in its markings, but when a blue bar mates with a blue bar, blue bar babies will always be produced. You see, when two recessives mate, that trait then becomes dominant. It wasn't finches that inspired Charles Darwin in his Origin of Species. It was pigeons. Darwin wrote a sonnet to them. I used to know it. He wanted a sense of how much variety existed with a single type of animal. At one time he had over 100 pigeons. When his daughter's cat got into his loft, he had the cat killed. He belonged to a prestigious pigeon club. A person had to be voted on by its members in order to be admitted. He wanted to show that a new species could be created from a common ancestor by the accumulation of small changes over generations. He believed that studying artificial selection of animals like pigeons would provide the evidence.

Mr. Heitzman's records were so complete that he could tell before two babies hatch, what colors they would be and everything about them. The most important thing to breed for is instinct. When a bird is found with that strong homing instinct and combined with condition, it will be a champion. Race horse people know and do the same thing.

Mr. Heitzman went over to one of his feed bins and lifted its cover and scooped out some mixed feed, spreading it inside a wooden, trough-like feed tray on the floor. The birds' beaks began pecking at individual seeds. There was a unison of pecking noises and heads bobbing with every bird hustling to gain a strategic position to eat. Each head was as quick as fingers racing in a typing class.

Mr. Heitzman went back out the door and down the steps with us following. We met an elderly man dressed in overalls, wearing a tilted blue and white striped engineer's cap. Mr. Heitzman introduced him as his full-time employed loft keeper. The man had been with Mr. Heitzman just like Herman had been with my grandfather. Mr. Heitzman asked that he grate a head of cabbage and meet us in the main stock loft. Walking on down over the hill towards a stand of woods along a creek, the stock loft appeared as though some tranquil home for the elves. It owned a round roof with a doweled aviary protruding from the front of it. The loft entered from the side, stepping through two doors. "The bird you caught will go in here," spoke Mr. Heitzman. "I already know who I will mate him to next year. I keep the males and females separated from July to February. I put them together on Valentine's day. Following nature is always best. I'm line breeding him back to Sion's Napoleon. It has been so long since a bird has been returned to me. When someone sees 'KY' on a bird's leg, he know its mine. I've had the KY bands since the end of the war. The American Racing Pigeon Union issues them solely to me. If one of my birds traps into another loft, I never hear about it. I suppose that's a compliment."

"My grandson is wanting to build a loft. Do you have any suggestions?" asked Grandfather.

"Lofts don't need to be big or heavy. My son flew pigeons in the Signal Corps during the war. Many of the birds I donated. They used portable lofts, and their birds stayed fine. Some of my favorite lofts in the back are from the war. Make your loft out of wood. You don't want concrete block, it will sweat. Moisture promotes sickness. Keep the loft off the ground. Make certain its well ventilated and face it to the south," Mr. Heitzman explained.

"How much do you get for a pair of pigeons?" asked Grandfather.

"A hundred dollars a pair for young birds. More for the old birds. If you all will come back next summer. I'll give you four youngsters. One out of the bird you returned. You'll never get better than that."

E. Lowell Robbins, Jr., 207 Longview Drive, Richmond, KY 40475; rrobbins6@juno.com, shares this article with our readers.